There’s been a lot of talk lately in the bustling world of journalism about why some newspaper and magazine content goes viral and other bits fall and fester. As the print industry slowly wanes, magazines and newspapers are hyperaware that online, they have greater control over how their content is received, thanks to quick turn over and tangible reader reaction (I hear these discussions all the time at my day job).

They all know that some of their content gets tweeted more than others. Some of it hits Digg like crazy, some shows up on Reddit.

Surely, there are some common denominators for the good stuff, right?

This is a question the magazines and news rags are all asking, all tightly crossing their fingers that some deeply mysterious algorithm exists that bears the secret to the Almighty Viral Content.

This problem is best approached in two steps.

First, why do people share?

Second, what do they share?

By attacking this problem via users and content, we get the best illustration of what’s actually going on. It’s all triangulation from there.

Cats. People share cats. Image by red.dahlia.

Cats. People share cats. Image by red.dahlia.

The New York Times, which has one of its articles tweeted every four seconds, recently went ahead and asked the first question — and asked it of Science.

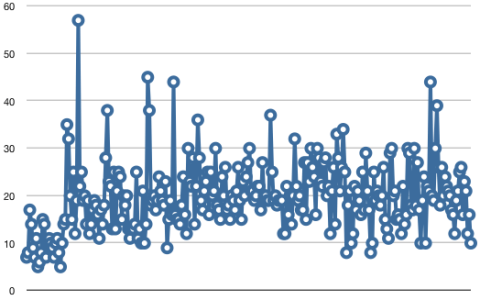

The tweet counts per minute of a New York Times article. Image from New York Times.

The tweet counts per minute of a New York Times article. Image from New York Times.

To complement this research, I invoke another study called What Makes Online Content go Viral published in the Journal of Marketing Research which attempts to address the second question.

Articles, videos and songs go viral because they engage their audiences, which is something any content officer should be concerned with. Dead content deadens users.

This isn’t a discussion to further hammer in the now-rather-trite idea that "content is king." What I hope to do here is to share what’s been discovered by marketers and researchers, and see what valuable bits web content developers can take away.

Too little science is covered in the web development community (this applies doubly in content-centered forums), and when it is, it’s often done so by someone trying to sell you on something.

But not this stuff, which is why you should read on.

The Research

When I discuss scientific research, I typically provide a series of caveats centered around the funders of the research, if applicable. For instance, check out this story about how dairy makes women stronger and less fatty. It was paid for by Big Dairy, which is a tiny conflict of interest.

But the two studies I’m talking about now exist in one of the rare areas where businesses and large organizations are paying for bona fide scientific and statistical research.

I say "rare" because, at this point, so little is understood about viral content patterns that no interest group stands to gain anything by tweaking the results; although The New York Times has sanctioned some of the most targeted research, they get nothing if the results simply say "content goes viral because Times’ articles are just awesome."

Granted, this is hardly an academic pursuit — many, many businesses stand to gain a great fat ton out of this type of information. But — and I truly hate to say it — one of the big differences between academic and privately driven research is how immediately practical it is.

So with these things in mind, let’s get to it.

Why Do People Share?

It probably comes as no surprise, but people share things to make themselves feel good, one way or another. It’s very human. It’s what we do.

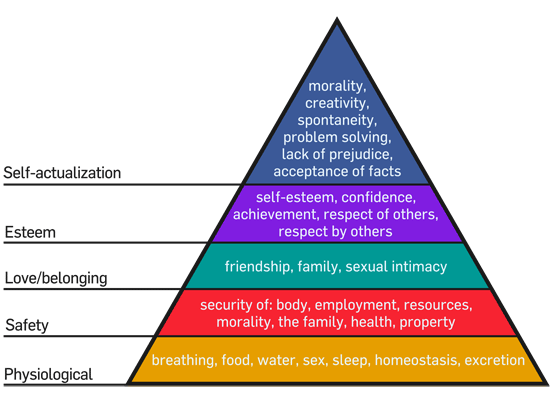

For those of you unfamiliar with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, once we have our physiological needs taken care of, we search for safety. Once we feel safe, we look for a sense of belonging. Then comes self-esteem. Finally, when all else is covered, we search for the "higher" concepts like morality, equality, and other idealistic "alities."

Image from Wikipedia.

Image from Wikipedia.

It’s the top two tiers of Maslow’s hierarchy that drive us to share — be it tweeting, watercooler chatter or half a cookie with friend. People want the respect of others, and they want to feel a sense of belonging.

And tweeting helps how, you might ask? Well, according to the NYT’s Consumer Insight Group, whose study consisted of 2,500 subjects, people are sharing content not only to "enrich the lives of others" in their online networks, but also to define themselves in whatever community they’ve taken part in. And we keep sharing to make sure we stay connected.

Of course, that’s a sweeping generalization. The study would be amiss without discussing the different types of sharers. These boil down to some basic personas.

Some people are more geared toward self-promotion, for instance. Others want to get the word out about some cause, and they use social media as a soapbox. Some people are just hipsters, and share things that make them more hipstery. (That’s seriously in the study mentioned earlier; not verbatim, but "hipsters" is a persona.) Others are hyper selective and only interact with a tight community.

But from hipsters to altruists, they all have those top two Maslow tiers urging their behavior.

What Do People Share?

Think about any recent content you’ve shared. Clearly, if you were driven to share it, it struck you as worth it. Let’s see, for me it was a scientific article about researchers making mouse embryos transparent. The one before that was an io9 article about Neil Patrick Harris guesting on Cartoon Network’s Adventure Time.

I shared these things for a number of reasons, but it all boils down to what the researchers in the virality study call emotional valence.

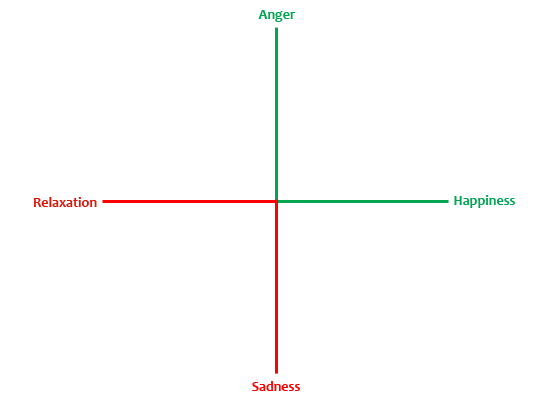

Think of this as graph: on the y-axis, you’ve got anger and sadness, the latter being on the negative end. On the x-axis are happiness and relaxation.

Both "positive" values — anger and happiness — are factors that are very good indicators of what gets passed around the Web.

The more highly charged those "positive" emotions, the better the chance. People want to be surprised and shocked, too (hence the old journalism adage, "If it bleeds, it leads"). And almost universally, people want to laugh.

So What?

These studies have narrowed down the characteristics that make content resonate with readers; I urge content wizards and wranglers to read the studies in full. I’ve by no means been exhaustive here.

As with a lot of psychological or statistical research into human behavior, much of this might strike you as intuitively obvious. It did for me.

But what’s not obvious is how anyone dealing with the direction of Web content should learn from this.

Viral content goes viral because it hits people upside the head, which is good.

It’s not forced. Just ask any marketer, business person or writer — no matter how much we’d love it, we can’t force content to hit home.

Keep viral characteristics in mind when developing and directing any content. All niche communities have their own versions of viral (Keyboard Cat, for instance, might not be super relevant to the antique tractor collector community), so as always, user research is the keystone no matter the content.

Writers must know their audience. Web and content developers, their users.

Related Content

- The Importance of Web Content Strategy

- The Web Strategy Pyramid: A Well-balanced Web Strategy

- Five Social Media Mistakes That Suck

- Related categories: Content Strategy and Website Management

About the Author

Kristina Bjoran is a science writer based in San Francisco, California. She works in editorial at Wired magazine and is a managing editor at UX Booth. Connect with her on Twitter, Facebook and Google+.

Kristina Bjoran is a science writer based in San Francisco, California. She works in editorial at Wired magazine and is a managing editor at UX Booth. Connect with her on Twitter, Facebook and Google+.