‘Cept Banana Is Weird in English Too

Via: made it myself

When I asked a class of prospective teachers to discuss the impact on students of prescriptive rules like “Don’t split infinitives,†“Don’t end sentences with prepositions,†and “Don’t use contractions,†one student ignored the descriptive grammar we had been studying and instead equated correctness in language with intelligent design:

I think I support prescriptivism. I believe that some words are absolutely unacceptable in any situation. I think there should be an accepted way of speaking and deviation would not be tolerated. I believe in a set of absolute values. I believe there is one right and wrong for everyone. Perhaps what I think is right is not what you think is right but in the final analysis that isn’t going to matter. What God thinks is right is what really matters and He doesn’t have one right for you and one right for me.

Her faith-based answer, God speaks standard English so you should too, may be extreme, but her emphasis on correct language is one that too many English teachers accept without question. So far as grammar lessons go, it’s time they stopped teaching that the earth is flat.

Even though creationists attack evolution as “just a theory,†high school biology covers the origin of species, along with DNA, microbes and the circulatory system. Physics teaches the big bang, subatomic particles, and as even Galileo knew 400 years ago, an earth that moves around the sun. And students in chem labs aren’t turning lead into gold, except perhaps at Hogwarts. There are no fundamentalist wingnuts enforcing the view that the rules of English are written in stone, yet English teachers act like the study of language hasn’t advanced since eighteenth-century grammarians started making lists of good grammar and bad or decided that a noun is the name of a person, place, or thing.

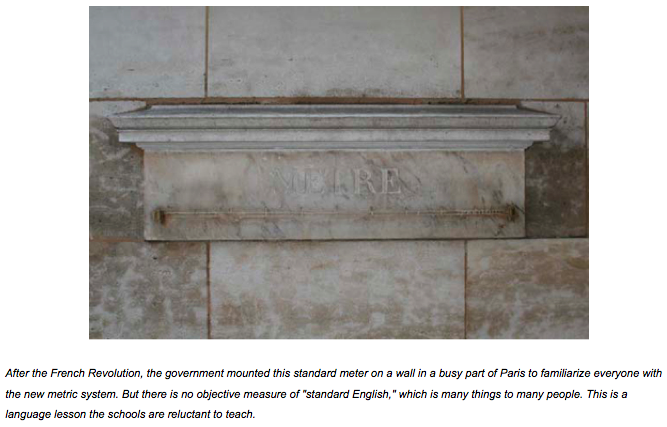

It’s not that English teachers don’t know that linguistic knowledge has progressed over the past 250 years. Prospective teachers get a healthy dose of sociolinguistics, transformational grammar, and the history of English. They study the emergence of dialects and the social contexts from which language standards grow. And they learn that unlike the standard meter or kilogram, which can be measured with scientific precision, there is no single, objective standard language which everybody speaks. They study language contact, assimilation, and heritage language loss, and they learn that when schools abandon bilingual education and leave non-English-speaking students to sink or swim in English-only classes, most sink. And last but not least, they’re taught to regard their students’ language not as something to be constantly graded and corrected, but as an energetic, highly-competent, continually-evolving form of language, complete with its own standards and variants.

But when they get their own classrooms, many of these same teachers reject such knowledge in favor of the simplistic language model they absorbed when they were in school, a model that ignores the complexities of the language people use every day in favor of a few prescriptive rules that can be memorized and tested, but that have little connection with what really happens when we talk or write.

Galileo, sitting in a science class today, would be mystified by a curriculum that has gone way beyond his experiment with an inclined plane, but Apollonius, the 2nd-century CE Greek grammarian who was one of the first to write about the parts of speech, would be perfectly at home with a modern grammar lesson, assuming he could follow it in English. And speaking of immigrants, if we could actually transport Apollonius and Archimedes, the Greek mathematician who first described the principle of buoyancy, to the local high school, they might find themselves sinking in an English-only immersion program.

For years linguists have been trying with little success to bring school grammar back to the present. We’re not proposing to do away with notions of correctness — ideas about appropriate usage form an important part of the way that English speakers function. Instead, we’d like to transmute the conventional right-wrong language dichotomy into a contextually-dependent sliding scale of language that works in particular situations, and language that may not work so well, demonstrating that there are many varieties of standard English, not just one. Plus, we’d like to point out that even in an English-speaking country, the language people use doesn’t always have to be English.

Unfortunately our schools have always been too focused on enforcing and testing a monolithic model of standard English to encourage teachers and their students to explore the language phenomena that surround us. As a result, teachers find it easier to tell students simply to avoid the passive voice than to get them to understand that although the passive can be problematic, it’s often useful and sometimes mandatory.

But even with the simplistic rule, “the passive should be avoided,†it turns out that many students can’t figure out the difference between the passive voice and the past tense. So in the end, standard English, which may or may not actually exist, often remains a mystery, and too many students leave school convinced that whether or not language is the product of intelligent design, its design is far from intelligible to them.

Luckily, outside the classroom things linguistic are neither obscure nor monochromatic. It’s true that when put on the spot, most people will parrot what they learned in school, that there’s a right and a wrong way to speak or write. But mostly people take a practical approach to correctness in language, recognizing as correct what works in a given context, not what’s categorically good or bad.

Perhaps the most important grammar lesson to learn, then, is to trust our language instincts instead of mimicking some ideal which turns out to be a moving target. We need to finally leave the eighteenth-century prescriptions behind and aim for language that is simply good enough to do the job of expressing whatever it is we need to say. And when we study language, we should study what it is, not what someone thinks it should be.

Dennis Baron is Professor of English and Linguistics at the University of Illinois. His book, A Better Pencil: Readers, Writers, and the Digital Revolution, looks at the evolution of communication technology, from pencils to pixels. You can view his previous OUPblog posts here or read more on his personal site, The Web of Language, where this article originally appeared. Until next time, keep up with Professor Baron on Twitter: @DrGrammar.

Posted in Google Reader

ChocoTheme by .css{mayo} | powered by WordPress