The following is an article from Uncle John’s Giant 10th Anniversary Bathroom Reader.

The following is an article from Uncle John’s Giant 10th Anniversary Bathroom Reader.

The media’s power to “create†news has become a hot topic in recent years. But it’s nothing new. This true story, from a book called The Fabulous Rogues, by Alexander Klein, is an example of what’s been going on for at least a century. It was sent to us by BRI reader Jim Morton.

Most journalistic hoaxes, no matter how ingenious, create only temporary excitement. But in 1899 four reporters in Denver, Colorado, concocted a fake story that, within a relatively short time, made news history -violent history at that. Here’s how it happened.

THE DENVER FOUR

One Saturday night the four reporters -from Denver’s four newspaper, the Times, Post, Republican, and Rocky Mountain News- met by chance in the railroad station where they had each come hoping to spot an arriving celebrity around whom they could write a feature. Disgustedly, they confessed to one another that they hadn’t picked up a newsworthy item all evening.

“I hate to go back to the city desk without something,†one of the reporters, Jack Toumay, said.

“Me, too,†agreed Al Stevens. “I don’t know what you guys are going to do, but I’m going to fake. It won’t hurt anybody, so what the devil.â€

They other three fell in with the idea and they all walked up Seventeenth Street to the Oxford Hotel, where, over beers, they began to cast about for four possible fabrications. John Lewis, who was known as “King†because of his tall, dignified bearing, interrupted one of the preliminary gambits for a point of strategy. Why dream up four lukewarm fakes, he asked. Why not concoct a sizzler which they would all use, and make it stick better by their solidarity.

The strategy was adopted by unanimous vote, and a reporter named Hal Wiltshire acme up with the first suggestion: Maybe they could invent some stiff competition for the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company by reporting the arrival of several steel men, backed by an independent Wall Street combine, come to buy a large site on which they planned to erect a new steel mill. The steel mill died a quick death; it could be checked too easily and it would be difficult to dispose of later.

Stevens suggested something more dramatic: Several detectives just in from New York on the trail of two desperados who had kidnapped a rich heiress. But this story was too hot; the editors might check the wire services or even the New York City police directly.

Thereupon Toumay and Lewis both came up with the obvious answer. What they needed was a story with a foreign angle that would be difficult to verify. Russia? No, none of them knew enough about Russia to make up an acceptable story. Germany was a possibility or perhaps, a bull-ring story from Madrid? Toumay didn’t think bull-fighting was of sufficient interest to Denverites. How about Holland, one of the reporters offered, something with dikes or windmills in it, maybe a romance of some sort.

THE PLOT THICKENS

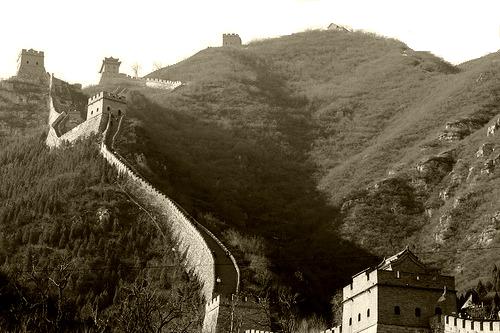

By this time the reporters had had several beers. The romance angle seemed attractive. But one of the men thought Japan would be a more intriguing locale for it. Anther preferred China; why, the country was so antiquated and unprogressive, hiding behind its Great Wall, they’d be doing the Chinese a favor by bringing some news about their country to the outside world.

At this point, Lewis broke in excitedly. “That’s it!†he cried, “The Great Wall of China! Must be fifty years since that old pile’s been in the news. Let’s build out story around it. Let’s do the Chinese a real favor, let’s tear the old pile down!â€

Tear down the Great Wall of China! The notion fascinated the four reporters. It would certainly make the front page. One of them objected that there might be repercussions, but the others voted him down. They did, however, decide to temper the story somewhat.

A group of American engineers had stopped over in Denver en route to China, where they were being sent at the request of the ruling powers of China, to make plans for demolishing the Great Wall at minimum cost. The Chinese had decided to raze the ancient boundary as a gesture of international goodwill. From now on China would welcome foreign trade.

By the time they had agreed on the details it was after eleven. They rushed over to the best hotel in town, and talked the night clerk into cooperating. Then they signed four fictitious names to the hotel register. The clerk agreed to tell anyone who checked that the hotel had played host to four New Yorkers, that they had been interviewed by the reporters, and then had left early the next morning for California. Before heading for their respective city desks, the four reporters had a last beer over which they swore to stick to their story and not to reveal the true facts so long as any of the others were alive. (Only years later did the last survivor, Hal Wiltshire, let out the secret.)

The reporters told their stories with straight faces to their various city editors. Next day all four Denver newspapers featured the story on the front page. Typical of the headlines was this one from the Times:

GREAT CHINESE WALL DOOMED!

PEKING SEEKS WORLD TRADE!

THE SNOWBALL EFFECT

Within a few day Denver had forgotten all about the Great Wall. So far, so good. But other places soon began to hear about it. Two weeks later Lewis was startled to find the coming destruction of the Great Wall spread across the Sunday supplement of a large eastern newspaper, complete with illustrations, an analysis of the Chinese government’s historic decision -and quotes from a Chinese mandarin visiting in New York, who confirmed the report.

The story was carried by many other newspapers, both in America and in Europe. By the time it reached China it had gone through many transformations. The version published there- and the only one that probably made sense in view of the absence of any information on the subject from the Chinese government -was that the Americans were planning to send an expedition to tear down the Chinese national monument, the Great Wall.

The story was carried by many other newspapers, both in America and in Europe. By the time it reached China it had gone through many transformations. The version published there- and the only one that probably made sense in view of the absence of any information on the subject from the Chinese government -was that the Americans were planning to send an expedition to tear down the Chinese national monument, the Great Wall.

Such a report would have infuriated any nation. It led to particularly violent repercussions in China at that time. The Chinese were already stirred up about the issue of foreign intervention -Europeans powers were parceling out and occupying the whole country. Russia had recently gotten permission to run the Siberian Railway through Manchuria. A year previously, German marines had seized the port town of Kiachow, and set up a military and naval base there. France followed by taking Kwangchowan. England had sent a fleet to the gulf of Chihli and bullied China into leasing Weihaiwei, midway between the recent acquisitions of France and Germany.

Faced with this danger of occidental exploitation, possibly even partition, the Chinese government under Emperor Kwang-Hsu began to institute radical reforms, to remodel the army along more modern lines, and to send students to foreign universities to obtain vital technical training.

Faced with this danger of occidental exploitation, possibly even partition, the Chinese government under Emperor Kwang-Hsu began to institute radical reforms, to remodel the army along more modern lines, and to send students to foreign universities to obtain vital technical training.

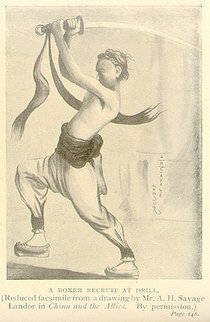

An important segment of Chinese society bitterly resented not only foreign intervention, but all foreign cultural influences, as well as the new governmental reforms. In 1889 Empress Tsu Hsi made herself regent and officially encouraged all possible opposition to Western ideas. A secret society known as the Boxers, but whose full name was “The Order of Literary Patriotic Harmonious Fists,†took the lead in verbal attacks on missionaries and Western businessmen in China by openly displaying banners that read “Exterminate the foreigners and save the dynasty.â€

THE SPARK THAT LIT THE FIRE

Into this charged atmosphere came the news of America’s plan to force the demolition of the Great Wall. It proved the spark that is credited with setting off the Boxer Rebellion. A missionary later reported: “The story was published with shouting headlines and violent editorial comment. Denials did no good. The Boxers, already incensed, believed the yarn and now there was no stopping them.â€

By June 1900, the whole country was overrun with bands of Boxers. Christian villages were destroyed and hundreds of native converts massacred near Peking. The city itself was in turmoil, with murder and pillage daily occurrences and the foreign embassies under siege.

Finally, in August, an international army of 12,000 French, British, American, Russian, German, and Japanese troops invaded China and fought its way to Peking. There, the troops not only brought relief to their imperiled countrymen, but also looted the Emperor’s palace and slaughtered innumerable Chinese without inquiring too closely whether they belonged to the “Harmonious Fists†or just happened to be passing by. The invading nations also forced China to pay an indemnity of $320 million and to grant further economic concessions. All this actually spurred the reform movement, which culminated with the Sun Yat-Sen revolution in 1911.

Thus did a journalistic hoax make history. Of course, the Boxers might have been sparked into violence in some other fashion, or built up to it of their own accord. But can we be sure? The fake story may have well been the final necessary ingredient. A case could even be made that the subsequent history of China, right up to the present, might have been entirely different if those four reporters had been less inventive that Saturday night in the Hotel Oxford bar.

See also: The Great Moon Hoax, Human Oil (and Other Hoaxes), and Joey Skaggs, The Ultimate Hoax Meister.

_____________________________

Reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Giant 10th Anniversary Bathroom Reader, which comes packed with 504 pages of great stories.

Reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Giant 10th Anniversary Bathroom Reader, which comes packed with 504 pages of great stories.

Since 1988, the Bathroom Reader Institute had published a series of popular books containing irresistible bits of trivia and obscure yet fascinating facts.

If you like Neatorama, you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books – check ‘em out!