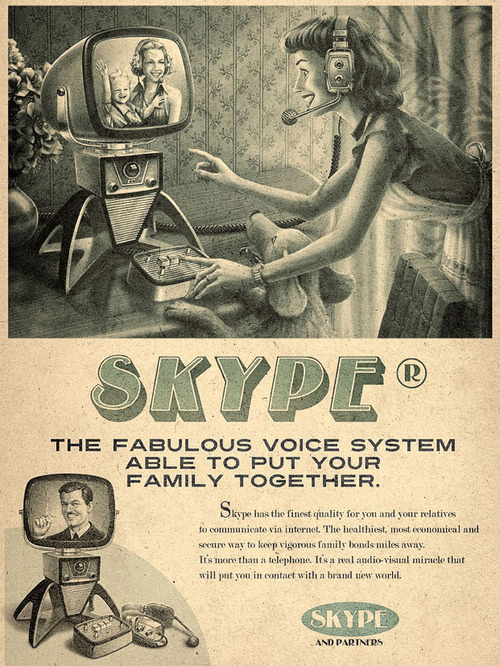

Brazil's Moma ad agency created a set of ads for newfangled tech companies in a mid-century style. [Ads of the World via Gawker]

Brazil's Moma ad agency created a set of ads for newfangled tech companies in a mid-century style. [Ads of the World via Gawker] Archive for August, 2010

Vintage-style ads for Facebook, Skype and YouTube

Brazil's Moma ad agency created a set of ads for newfangled tech companies in a mid-century style. [Ads of the World via Gawker]

Brazil's Moma ad agency created a set of ads for newfangled tech companies in a mid-century style. [Ads of the World via Gawker] Triceratops controversy shakes paleontology to its bones [Mad Paleontology]

Cool Photos and Artworks for Your Inspiration #21

This post is part of our weekly series: showing some interesting Photos and Artworks around the Web so you can get inspiration for your design. If you want to share your great Photos or Artworks with our readers, just send them over via email with image source link using “Weekly Photos and Artworks Inspiration†in the subject. Enjoy the post.

If you see a photo or artwork that is yours and you want credit or it to be taken off, just let us know. We don’t take credit for any of these, this post is just for collecting cool photos and artworks for design inspiration.

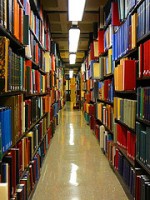

There Are 129,864,880 Different Books in the World

Google, which is engaging in extensive book digitization projects, recently set out to determine the number of distinct print books currently in existence:

Google, which is engaging in extensive book digitization projects, recently set out to determine the number of distinct print books currently in existence:

After some intensive analysis, we’ve come up with a number. Standing on the shoulders of giants—libraries and cataloging organizations—and based on our computational resources and experience of organizing millions of books through our Books Library Project and Books Partner Program since 2004, we’ve determined that number.

As of today, we estimate that there are 129,864,880 different books in the world. That’s a lot of knowledge captured in the written word! This calculation used an algorithm that combines books information from multiple sources including libraries, WorldCat, national union catalogs and commercial providers. And the actual number of books is always increasing.

Link via Cool-O-Rama | Photo by Flickr user Nrbelex used under Creative Commons license

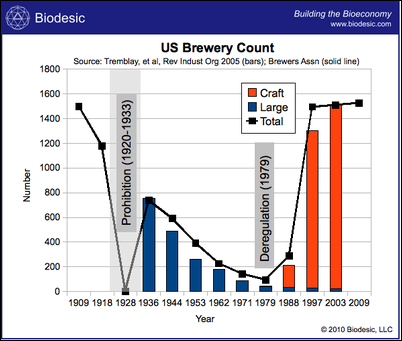

How Jimmy Carter Saved Beer

I am not a drinker, but this, per E.D. Kain, seems like an unappreciated accomplishment for the 39th president:

If you’re a fan of craft beer and microbreweries as opposed to say Bud Light or Coors, you should say a little thank you to Jimmy Carter. Carter could very well be the hero of International Beer Day.

To make a long story short, prohibition led to the dismantling of many small breweries around the nation. When prohibition was lifted, government tightly regulated the market, and small scale producers were essentially shut out of the beer market altogether. Regulations imposed at the time greatly benefited the large beer makers. In 1979, Carter deregulated the beer industry, opening back up to craft brewers. As the chart below illustrates, this had a really amazing effect on the beer industry:

Â

Possibly this was all a plot to jack up peanut sales. But it worked.

It's worth noting that Carter got no political credit for this move, and that the benefits didn't appear until long after he departed. Some policy successes -- like a successful war or peace treaty -- yield immediate political dividends. But others produce little change until many years later, by which time everybody has forgotten your policy had anything to do with it.

We may have been looking at the wrong DNA for the secrets of longevity [Mad Genomics]

We Are All Talk Radio Hosts

Let me tell you a story about strawberry jam. In 1991, the psychologists Timothy Wilson and Jonathan Schooler decided to replicate a Consumer Reports taste test that carefully ranked forty-five different jams. Their scientific question was simple: Would random undergrads have the same preferences as the experts at the magazine? Did everybody agree on which strawberry jams tasted the best?

Wilson and Schooler took the 1st, 11th, 24th, 32nd, and 44th best tasting jams (at least according to Consumer Reports) and asked the students for their opinion. In general, the preferences of the college students closely mirrored the preferences of the experts. Both groups thought Knott’s Berry Farm and Alpha Beta were the two best-tasting brands, with Featherweight a close third. They also agreed that the worst strawberry jams were Acme and Sorrel Ridge. When Wilson and Schooler compared the preferences of the students and the Consumer Reports panelists, he found that they had a statistical correlation of .55. When it comes to judging jam, we are all natural experts. We can automatically pick out the products that provide us with the most pleasure.

But that was only the first part of the experiment. The psychologists then repeated the jam taste test with a separate group of college students, only this time they asked them to explain why they preferred one brand over another. As the undergrads tasted the jams, the students filled out written questionnaires, which forced them to analyze their first impressions, to consciously explain their impulsive preferences. All this extra analysis seriously warped their jam judgment. The students now preferred Sorrel-Ridge—the worst tasting jam according to Consumer Reports—to Knott’s Berry farm, which was the experts’ favorite jam. The correlation plummeted to .11, which means that there was virtually no relationship between the rankings of the experts and the opinions of these introspective students.

What happened? Wilson and Schooler argue that “thinking too much†about strawberry jam causes us to focus on all sorts of variables that don’t actually matter. Instead of just listening to our instinctive preferences, we start searching for reasons to prefer one jam over another. For example, we might notice that the Acme brand is particularly easy to spread, and so we’ll give it a high ranking, even if we don’t actually care about the spreadability of jam. Or we might notice that Knott’s Berry Farm has a chunky texture, which seems like a bad thing, even if we’ve never really thought about the texture of jam before. But having a chunky texture sounds like a plausible reason to dislike a jam, and so we revise our preferences to reflect this convoluted logic.

And it’s not just jam: Wilson and others have since demonstrated that the same effect can interfere with our choice of posters, jelly beans, cars, IKEA couches and apartments. We assume that more rational analysis leads to better choices but, in many instances, that assumption is exactly backwards.

These studies represent an important reevaluation of the human reasoning process. Instead of celebrating our analytical powers, these experiments document our foibles and flaws. They explore why human reason can so often lead us to believe blatantly irrational things, or why it’s reliably associated with mistakes like cognitive dissonance or confirmation bias. And this leads me to a wonderful new paper by Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber (I found it via this insightful talk by Jonathan Haidt) that summons a wide range of evidence – such as the strawberry jam study above – to argue that human reason has nothing to do with finding the truth, or locating the best alternative. Instead, it’s all about argumentation. Here’s their abstract:

Reasoning is generally seen as a mean to improve knowledge and make better decisions. Much evidence, however, shows that reasoning often leads to epistemic distortions and poor decisions. This suggests rethinking the function of reasoning. Our hypothesis is that the function of reasoning is argumentative. It is to devise and evaluate arguments intended to persuade. Reasoning so conceived is adaptive given human exceptional dependence on communication and vulnerability to misinformation. A wide range of evidence in the psychology or reasoning and decision making can be reinterpreted and better explained in the light of this hypothesis. Poor performance in standard reasoning tasks is explained by the lack of argumentative context. When the same problems are placed in a proper argumentative setting, people turn out to be skilled arguers. Skilled arguers, however, are not after the truth but after arguments supporting their views. This explains the notorious confirmation bias. This bias is apparent not only when people are actually arguing but also when they are reasoning proactively with the perspective of having to defend their opinions. Reasoning so motivated can distort evaluations and attitudes and allow the persistence of erroneous beliefs. Proactively used reasoning also favors decisions that are easy to justify but not necessarily better. In all of these instances traditionally described as failures or flaws, reasoning does exactly what can be expected of an argumentative device: look for arguments that support a given conclusion, and favor conclusions in support of which arguments can be found.

Needless to say, this new theory paints a rather bleak portrait of human nature. Ever since the Ancient Greeks, we’ve defined ourselves in terms of our rationality, the Promethean gift of reason. It’s what allows us to make sense of the world and uncover all sorts of hidden truths. It’s what separates us from other Old World primates. But Mercier and Sperber argue that reason has nothing to do with reality. Instead, it’s rooted in communication, in the act of trying to persuade other people that what we believe is true. And that’s why thinking more about strawberry jam doesn’t lead to better jam decisions. What it does do, however, is provide up with more ammunition to convince someone else that the chunky texture of Knott’s Berry Farm is really delicious, even if it’s not.

The larger moral is that our metaphors for reasoning are all wrong. We like to believe that the gift of human reason lets us think like scientists, so that our conscious thoughts lead us closer to the truth. But here’s the paradox: all that reasoning and confabulation can often lead us astray, so that we end up knowing less about what jams/cars/jelly beans we actually prefer. So here’s my new metaphor for human reason: our rational faculty isn’t a scientist – it’s a talk radio host. That voice in your head spewing out eloquent reasons to do this or do that doesn’t actually know what’s going on, and it’s not particularly adept at getting you nearer to reality. Instead, it only cares about finding reasons that sound good, even if the reasons are actually irrelevant or false. (Put another way, we’re not being rational – we’re rationalizing.) While it’s easy to read these crazy blog comments and feel smug, secure in our own sober thinking, it’s also worth remembering that we’re all vulnerable to sloppy reasoning and the confirmation bias. Everybody has a blowhard inside them. And this is why it’s so important to be aware of our cognitive limitations. Unless we take our innate flaws into account, the blessing of human reason can easily become a curse.

Image: The Image Spot

What Everyone Knows

Everyone knows.... that you should make your bed

Everyone knows.... that you should make your bed

Everyone knows... that you should wash chicken before you cook it

Everyone knows... that mayonnaise goes bad quickly

Everyone knows... that what we used to know is wrong, but what we know now is correct.

People are often wrong. Experts are only as good as their knowledge, observations, and ability to interpret what they see. In the three cases above, studies and new thinking have replaced "what everyone knows" with new knowledge – and they're all false.

While making your bed may seem tidy, it's been known by scientists for years that making your bed increases the growth of mites. During the night, you sweat and that moisture is absorbed by the bed. In turn this moisture provides a hospitable environment for the mites who breed and multiply as they feed on your dead skin cells. If their concentrations get too high, you may experience itchiness or other symptoms from their excrement. For the best results, don't make your bed, which helps it dry out during the day.

As for chicken, it's also been known for years that washing raw chicken increases the likelihood of food poisoning. Why? Because chicken meat and skin are often covered with harmful pathogens. While cooking the chicken kills these pathogens, washing the chicken just spreads them around to the sink, counter, cutting board... and your hands. It's far better to handle the chicken as little as possible and then wash your hands and anything else that has come into contact with the chicken.

And if you're choosing to make chicken salad out of that chicken, know that mayonnaise is a preservative, not something that makes the chicken go bad faster. Mayonnaise has a pH of 3.7, which is acidic enough to retard the growth of most bacteria. That doesn't mean food should be left out – bacteria will grow eventually. Just know that if you get sick, it was likely the chicken's fault rather than the mayo.

Don't believe me? See what Google says. And see what we've known for years.

Except that we haven't, have we? I'll wager that many of you believed some if not all of these pieces of wisdom. The fact that they're "time-honored" and dare I say "ancient wisdom" has no bearing on the fact that according to the best information we have available today, they're all false.

Yet many would claim that we not update what we "know" based on new information. Purveyors of "ancient arts" like homeopathy, Ayurveda, bloodletting, the four humors, acupuncture, and phrenology fail to embrace this idea.

Science is not about what we know, but about how we know. And we know that as we gather more information, we'll have a more accurate view of the way the world works.

And that means... I don't have to make my bed anymore. Yay science!

Gamers beat algorithms at finding protein structures

Today's issue of Nature contains a paper with a rather unusual author list. Read past the standard collection of academics, and the final author credited is... an online gaming community.Â

Scientists have turned to games for a variety of reasons, having studied virtual epidemics and tracked online communities and behavior, or simply used games to drum up excitement for the science. But this may be the first time that the gamers played an active role in producing the results, having solved problems in protein structure through the Foldit game.

According to a news feature on Foldit, the project arose from an earlier distributed computing effort called Rosetta@home. That project used what has become the standard approach for home-based scientific work: a screensaver that provided a graphical frontend to a program that uses spare processor time to solve weighty scientific problems. For Rosetta, that problem was the task of figuring out how proteins, which are composed of a chain of chemicals called amino acids, adopt their final, three-dimensional shape.

Read the comments on this post