Fun Fact of the Day: Also, the word bed looks like a bed.

[@petergriffin / nerdvana / thd.]

Tagged: boobs, Fun Fact, Peter Griffin, Webcomic

Fun Fact of the Day: Also, the word bed looks like a bed.

[@petergriffin / nerdvana / thd.]

According to this infographics, created by Jess B. who submitted it, you can compare apples and oranges.

Fun stuff. The entire chart is here.

***

Advice to marketers trying to reach "Edward": You might want to check out Ask ET. Your chance of getting mentioned here drops drastically if you can't figure out who's writing this blog.

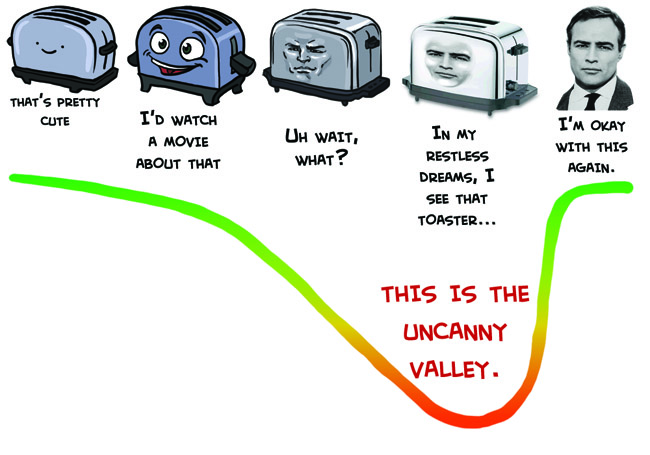

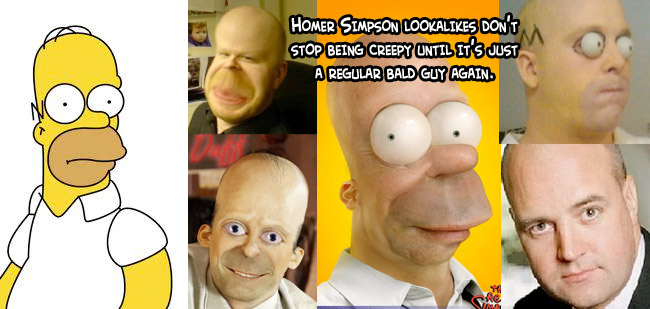

It seems from the comments on the Duke Nukem comic that a lot of people don’t really understand what Uncanny Valley is, or why it’s horrible and creepy and something no designer should approve of unless they’re in the horror business (in which case you need to push it to the limit). “Uncanny Valley†does not necessarily refer to things that are trying to be realistic, nor does it mean “anything you think is uglyâ€. Specifically, the term “Uncanny Valley†was meant to refer to robots, saying that people will like things that look like obvious abstractions of people, and people will like things that look exactly like people, but people are repulsed by things that look almost like people but not quite.

You can hit up the Wikipedia page on the matter for an in-depth explanation of exactly what it means, but I broke it all down into easily digestible pictures of how this all relates to design because I felt like drawing toasters and gluing eyes on lions when I got home from work today.

If we made a graph of how much people enjoy watching something move around VS level of realism, the “Uncanny Valley†is that dip where something is too much like a person without actually looking like a person for people to respond positively to it. It’s basically why Tweenbots and Arnold Schwarzenegger have an easier time making friends than the Japanese speaking robot mouth thing.

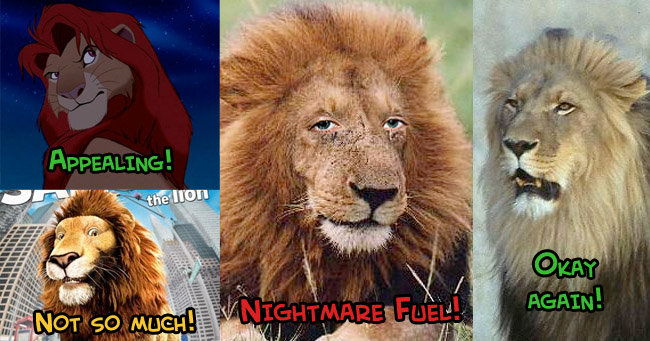

If you want something non-human to emote like a human, you can’t just slap human eyes on it and call it a day. Back in the day sometime in first year animation class we were doing four-legged animal walk cycles, of animals randomly chosen out of a hat. The teacher warned us that people who got things like cats and dogs were probably going to have a harder time than people who got things like bears and raccoons, because people are so familiar with those animals that they’ll always notice right away if something looks wrong. This goes for anything people have a point of reference for. I would assume that furry art wouldn’t be quite as popular as it is if the cute cartoon girls were replaced with realistic human-animal mashups, at least.

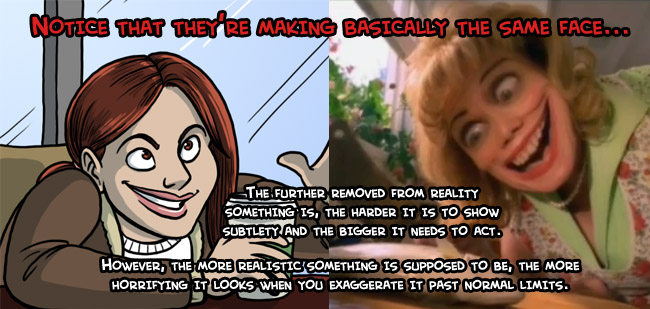

It’s important to understand the limits of a style you’ve chose to work in. Realistic designs have to move realistically, stylized cartoons have to move like cartoons. Disney’s Cinderella can’t make the same boisterous exaggerated acting that her stepsisters do because her design is so much more conservative than theirs that it would look absurd and out of place. When cartoony characters move like humans, you get that cheap rotoscope/mo-cap look, but when real people move like cartoons you get the Black Hole Sun music video;

Which nicely segues into the rule of uncanny valley that most CG studios seem to be actively ignoring these days, which is that things should only have realistic texture if they have realistic proportions. Personally, I really hate the idea that cartoon animals should have hyper realistic fur. It makes them look like kids’ plush animals made out of real animal pelts (This is a real thing I have seen done, there is no worse way to show off that prized lynx you bagged than by skinning it and making a plush bunny out of it). Peter Jackson is all excited to talk about his realistic CG Tintin movie where you’ll be able to see all of Tintin’s pores and hair follicles, but honestly, cartoon characters with human skin stretched over them just look horrible.

This is all really informal and I didn’t really have a conclusion planned, so I’ll just remind you to look at the Muppets with People Eyes tumblr every time you start feeling like Uncanny Valley isn’t all that bad.

I finally got a chance to take a closer look at O'Reilly's most recent edition to their "Beautiful" series, Beautiful Visualization: Looking at Data through the Eyes of Experts, and it's a good one. In case you're not familiar, each book in the series is a collection of essays from people who work in the field. Essays range in topic, but they usually focus on a single project and discuss the steps it took to make said project. To be clear, Beautiful Visualization isn't a how-to book, although you can learn a lot from the writings.

I finally got a chance to take a closer look at O'Reilly's most recent edition to their "Beautiful" series, Beautiful Visualization: Looking at Data through the Eyes of Experts, and it's a good one. In case you're not familiar, each book in the series is a collection of essays from people who work in the field. Essays range in topic, but they usually focus on a single project and discuss the steps it took to make said project. To be clear, Beautiful Visualization isn't a how-to book, although you can learn a lot from the writings.

When I first received Beautiful Visualization in the mail and opened up the package, it was smaller than I expected. Height and width are the same as the previous Beautiful Data, but it's about a third smaller in depth. However, I realized that's just because they use a different kind of paper (without feeling cheap) and it actually has about twenty more pages than Beautiful Data, coming in at just under 400. All of the images are in full color and big enough so that you can make out the details.

There are 20 chapters, or essays rather, by 24 authors. The lineup will tip you off on what you're in for, and many of the names will sound familiar, as they've been mentioned on FD on more than several occasions. There were a few names on the list that I didn't recognize, but it's clear that everyone enjoys what they do, and more importantly, enjoy playing with data.

Noah Illinsky, who edited the book with Julie Steele, sets the stage with the first chapter on what is meant by beautiful visualization. Then the rest of the essays get into specific projects and datasets.

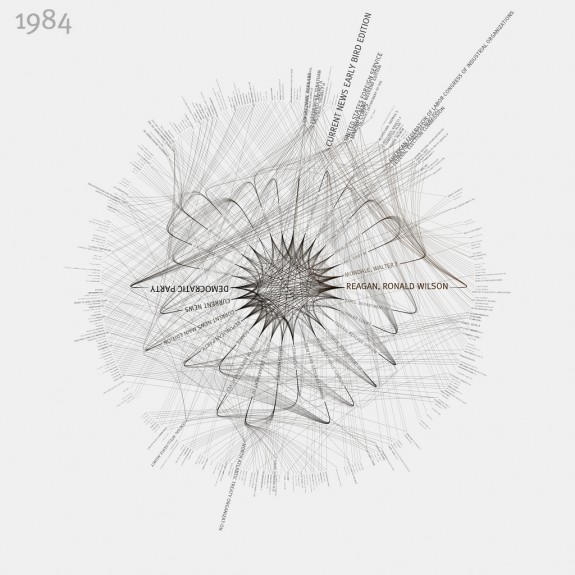

For example, Jer Thorp, who was the data artist in residence at the New York Times over the summer, goes into how he made use of the New York Times API.

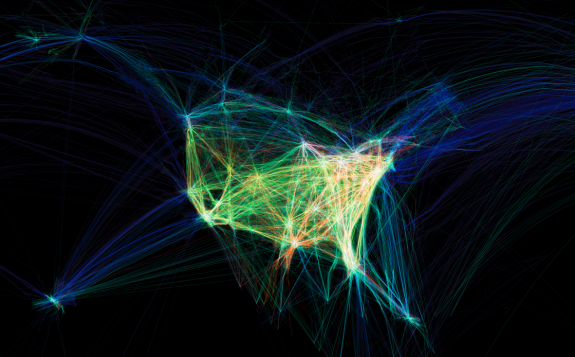

Aaron Koblin, whose work below we all know I am sure, dives into Flight Patterns and how he got into exploring 24 hours worth of flight data.

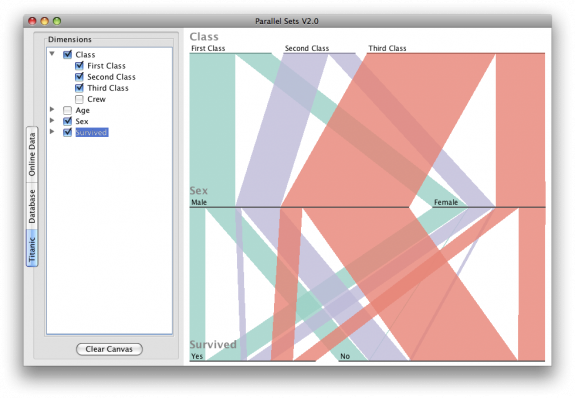

Robert Kosara explains the process of parallel sets.

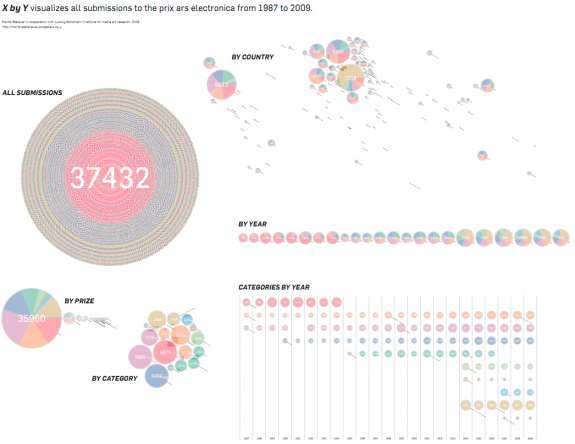

Moritz Stefaner explored submissions to the prix ars electronica over several decades.

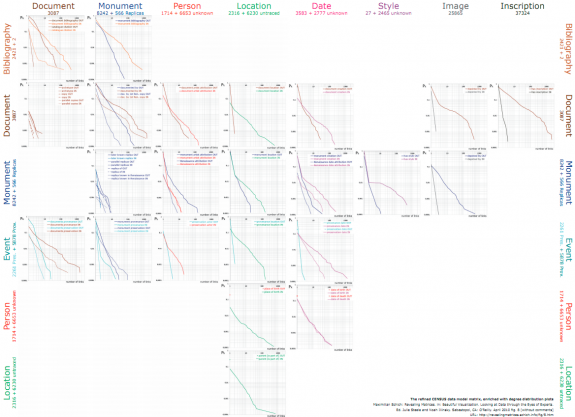

Maximilian Schich uses data matrices to uncover patterns in heterogenous data.

Martin Wattenberg and Fernanda Viegas also describe History Flow, their visualization to show Wikipedia edits, Jessica Hagy briefly covers her index cards, and several others go into detail about how they did things.

While visualization can get very technical, the authors do a good job of keeping things abstract enough so that you know what they're talking about even if you're not particularly experienced in the field. They provide enough detail though that it's still interesting for others.

A lot of people who are interested in visualization think that's it's a matter of learning a bunch of tools, but there's a lot more to it than that. You're also learning about data, and learning what questions to ask, and if you don't know what questions to ask, you just end up with visualization that doesn't really mean anything. Design also plays a role in in conveying the message you want. So it's great that there's a resource that can help you get into the experts' heads.

If anything, it's just fun to read about the process of how a graphic or tool gets made. For example, Jonathan Feinberg, who designed the ever popular Wordle, explains what went into the work. Some people like to knock it, but he knows plenty well that the stylized word clouds aren't the best way to visualize data or extract information, or whatever.

I'll tell you what this book isn't. It's not a how-to book. It's not a showcase book with screenshots of a bunch of out-of-context projects. Rather, Beautiful Visualization tells you how some well-known visualizations were made. I do wish there was at least one essay from a pure statistician like Di Cook, but other than that, the author group is a good one. All in all, it's a good read with interesting subject matter. Thumbs up.

Why haven’t we seen the internet transform education yet?

Music, movies, publishing, software and basically every industry reliant on information is being turned upside down. Having collections of tens of thousands of songs isn’t uncommon now. Being able to watch any movie ever made is easy and getting news minutes within it happening is almost an expectation.

Why, then, do most people who want to learn something seriously still go to school? Why has the web seemingly left higher education untouched?

Will the Web Kill School?

At first the idea seems absurd. Of course people will still go to school, how could they not?

But how many people would have properly guessed that record labels would be crippled or that amateur bloggers would be threatening the job security of experienced journalists? Just because something has been a tradition doesn’t mean it’s immortal.

The problem isn’t technical limitations. Many universities already offer online courses. While distance education classes are often shabbier than classroom productions, that’s an issue of scale, not a fundamental limit on the technology.

Some would argue that the personal touch is necessary for universities. But why? What percentage of student time is spent actually mutually interacting with a professor? Even 10% seems generous.

In that case, why couldn’t the other 90% be produced by the absolute best lecturers or textbook writers. This would make the interactive teaching role the equivalent of the music industry’s concerts, unscalable by the web, but ultimately only a minority of actual consumption.

Imagine if every lecture was the quality of the best TED Talks? Or every textbook had the wit and clarity of a Malcolm Gladwell bestseller? If those were truly the options, why would universities be left unscathed in an internet revolution?

Why The .COM Diploma Doesn’t Exist Yet

If any industry needs a web-based revolution, it’s education. Tuition prices have outpaced inflation here in North America, and for many that means a lot of student debt. The situation is better in Europe, but that’s in part due to taxpayers paying for tuition costs.

However if much of the information content of education were distributed online, the costs could be lowered dramatically. Fees would mostly be for testing or occasional tutoring, far less than the institutional cost of managing an entire university.

So why don’t we see .COM Diplomas with entirely online resources and only nominal fees for testing and tutoring?

I believe the reason actually has nothing to do with education itself. That is, the reason expensive higher-education institutions have been mostly unscathed by the internet has little or nothing to do with the limitations on online education, but on the other function they serve: accreditation.

Universities degrees signal good qualities. If you have one, it means you’re probably intelligent, hard working and committed enough to invest a few years of your life. It also is a good barometer of field-specific knowledge. A degree in engineering means you probably understand the basics of engineering.

So far, only universities can bestow these degrees. Sure, there are purely online education certificates, but they don’t really compare to their offline equivalents.

But if accreditation and cultural signalling is the major barrier preventing purely online higher-education, it probably won’t last. As of today, most intelligent, hard-working people are going to university because it’s what hardworking, intelligent people do. If enough of those people decide to teach themselves using high-quality online resources—employers and culture will change which signals they look for.

How The Web Will Change Education (For the Better)

I don’t see anything fundamentally unscalable with most of what we consider education. Lectures? YouTube. Textbooks? Kindle. Group participation? Online forums.

Testing and tutoring seem to be two areas that would be harder to scale upwards. Testing, because some personal oversight would seem necessary to prevent cheating (although universities aren’t terribly good at this currently). Tutoring, because one-on-one teaching is still valuable even if in-class lectures could largely be replaced with streaming video.

With scalability, the cost structure of education changes. If an education resource will be viewed by millions of people, instead of the hundred or so present in a class, that means fixed costs can go up and prices can go down.

Fixed cost investments in education materials can go up when it costs nothing to provide another copy. Microsoft purportedly spent around $6 billion to develop Vista. And even with monopoly pricing, one edition costs only around $200. Imagine if the same ratios were used for classroom lectures.

Some critics might object that YouTube banality or Twitter attention-spans would infect online education, rendering it impotent against traditional formats. This is ridiculous. The reason little serious online education exists is because it currently lacks accreditation. Learning is hard and without recognition, I’ll probably opt for something easy.

But accreditation is about cultural expectations. If more smart, hard-working people opt to teach themselves online, employers and cultural norms will shift.

How Will Universities Be Affected?

I predict that the most prestigious schools will be hurt the least. Harvard, Yale and MIT will still be incredible brand names, even in a new education environment. Because of their selectivity and networking power of alumni, it may be that the most expensive schools offer the most value outside of the education itself.

Instead, I’m guessing that the low to medium prestige schools will be hurt the most. When online education becomes a radically more affordable version, perhaps with better quality instruction, materials and testing, it will be harder to justify tuition prices.

Looking online it seems as if many of the schools are already beginning to recognize this. MIT, Stanford and Harvard all have completely free, online versions of some of their popular classes. Yet I haven’t seen anything like this from less prestigious universities.

If we see a mass exodus from universities, what will that mean for research? Universities currently conduct much of the advancement of science and research. Will they complete the transformation into innovation centers for the pharmaceutical or high-tech industries? Or will governments have to step in to pay more of the cost of research currently being funded by students?

Institutions May Lose, But We Will Win

As with the music industry, I suspect a lot of the impending change on education will be needlessly be focused on the loss of old institutions. Media reports the saddening decline of record labels or newspapers.

But music hasn’t died and neither has journalism. People now listen to more music than ever before. I carry my iPod with me everywhere. News may be suffering, but it seems like the lowered quality of news is due more to the industry in its death throes, trying to clasp for interest, while distributed online sources become increasingly more credible.

If education goes online, universities may suffer, but education will not. Making education cheaper, better and more accessible will probably mean more educated people, particularly from the economic classes and regions that can currently least afford it.

When, Not If

I’m confident that the internet transforming education is a question of when, not if.

My guess is that for some people, this is a radical notion. The idea that institutions existing for hundreds of years will be forcibly transformed in the next decade or two seems implausible.

But for the people who already use the internet, my guess is that this prediction seems almost tame. For many people who watch TED talks, surf Wikipedia and expect knowledge at their fingertips, it’s already happening.

As an aside, I’m going to be in Austin for SXSW from the 11th until the 15th (this weekend). If you’re going to be there and want to meet up, please let me know. If there are enough people, I’ll try to set a meet-up!

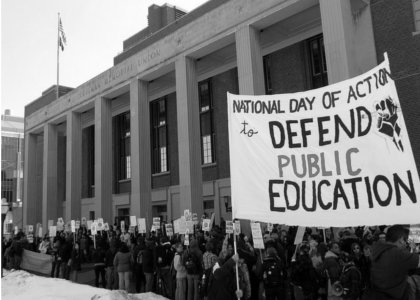

Image thanks to Fibonacci Blue

Learn Faster, Achieve More

Get the ideas I don't share on the blog. Join my private newsletter and I'll give you my free rapid-learning ebook.

Facebook recently announced the Comments Box Plugin. This new plugin allows you to add the Facebook Comments feature to any website.  The plugin makes it easy to include a comment thread on your website, allows for comment moderation, and integrates the Facebook login.

But the really cool thing is that when a user enters a comment on your site, that comment is reflected and synced in that user’s wall or news on Facebook. So not only will your existing website viewers see the comment, but all the people connected to the commentator can see it in Facebook.

The first image shows the comment box I added to a test page on my web site. I’ve signed into Facebook through the plugin, so it displays my profile picture and gives me the option to post my comment to Facebook.

After a user makes a comment on my website, the plugin posts a link to your website and the comment to that user’s Facebook wall. The second image shows

the comment posted to my Facebook news page. People viewing that user’s wall on Facebook can ‘like’ it and post their own comments. These ‘like’ votes and comments are then displayed back on your website automatically.

By implementing this simple social tool on your website, you have an instant way to connect your website with the vast number of Facebook users in a very non-threatening way.  Your website link will be exposed to all the friends of your commentators and you can view their comments on your website.

Be careful, though. The comment data is stored on Facebook, not your website. While you can moderate the comments, you may find that negative comments can go viral just like good comments.

Viral Marketing: Facebook Comments Right Inside Your Website

Comment Box Plugin running on my test page

Facebook recently announced the Comments Box Plugin. This new plugin allows you to add the Facebook Comments feature to any website.  The plugin makes it easy to include a comment thread on your website, allows for comment moderation, and integrates the Facebook login.

But the really cool thing is that when a user enters a comment on your site, that comment is reflected and synced in that user’s wall or news on Facebook. So not only will your existing website viewers see the comment, but all the people connected to the commentator can see it in Facebook.

The first image shows the comment box I added to a test page on my web site. I’ve signed into Facebook through the plugin, so it displays my profile picture and gives me the option to post my comment to Facebook.

After a user makes a comment on my website, the plugin posts a link to your website and the comment to that user’s Facebook wall. The second image shows

Comments displaying in Facebook

the comment posted to my Facebook news page. People viewing that user’s wall on Facebook can ‘like’ it and post their own comments. These ‘like’ votes and comments are then displayed back on your website automatically.

By implementing this simple social tool on your website, you have an instant way to connect your website with the vast number of Facebook users in a very non-threatening way.  Your website link will be exposed to all the friends of your commentators and you can view their comments on your website.

Be careful, though. The comment data is stored on Facebook, not your website. While you can moderate the comments, you may find that negative comments can go viral just like good comments.

Posted in Google Reader